Remember when we thought Covid was a two-week illness? So does Michael Peluso, assistant professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

He recalls the rush to study acute Covid infection, and the crush of resulting papers. But Peluso, an HIV researcher, knew what his team excelled at: following people over the long term.

So they adapted their HIV research infrastructure to study Covid patients. The LIINC program, short for “Long-term Impact of Infection with Novel Coronavirus,” started in San Francisco at the very beginning of the pandemic. By April 2020, the team was already seeing patients come in with lingering illness and effects of Covid — in those early days still unnamed and unpublicized as long Covid. They planned to follow people’s progress for three months after they were infected with the virus.

By the fall, the investigators had rewritten their plans. Some people’s symptoms were so persistent, Peluso realized they had to follow patients for longer. Research published Wednesday in Science Translational Medicine builds on years of that data. In some cases, the team followed patients up to 900 days, making it one of the longest studies of long Covid (most studies launched in 2021 or 2022, including the NIH-funded RECOVER program).

Investigators found long-lasting immune activation months and even years after infection. And, even more concerning, they report what looked like lingering SARS-CoV-2 virus in participants’ guts. Even those who’d had Covid but no continuing symptoms had different results than those who’d never been infected.

The team’s big idea — hypothesizing in early 2020 that, contrary to the popular narrative, Covid would last in the body — was “visionary,” long Covid researcher Ziyad Al-Aly said. “A lot of people don’t think like that.” Al-Aly was not involved with the study, but has published other long-term studies of Covid patients. He is chief of research and development at the VA Saint Louis Healthcare System.

The research makes use of novel technology developed by the paper’s senior authors, Henry Vanbrocklin, professor in the department of radiology at UCSF, and associate professor of medicine Timothy Henrich. They figured out in the last several years they could use an antibody that bound to HIV’s code protein as a guide to see viral reservoirs. The HIV antibody, labeled with radioactive isotopes, could be tracked with imaging as it moved through the body and migrated to infected tissues.

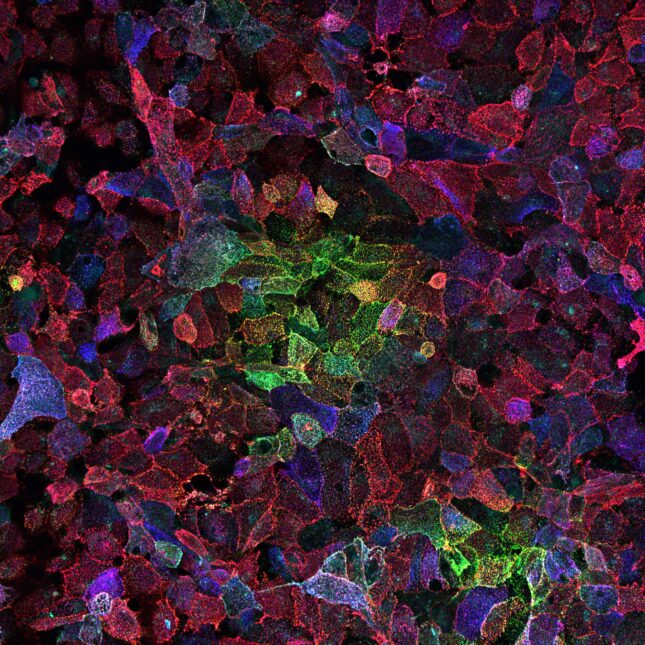

There were no antibodies to latch onto early in the coronavirus pandemic. Vanbrocklin instead used a chemical agent, called F-AraG, that binds to activated T cells — immune cells that flood into infected tissues. They injected F-AraG into patients, and into a scan they went.

Tissues full of activated T cells glowed in the resulting image. Researchers found more glowing sites of immune activation in people who had been infected with Covid than in those who had not, including: the brain stem, spinal cord, cardiopulmonary tissues, bone marrow, upper pharynx, chest lymph nodes, and gut wall.

In people with long Covid symptoms, like brain fog and fatigue, the study found the gut wall and spinal cord lit up more than in other participants. People with continuing pulmonary symptoms showed greater immune activation in their lungs. Gut biopsies in five participants revealed what appears to be persistent virus, said Peluso, who is part of the LongCovid Research Consortium of the PolyBio Research Foundation (which helped fund the study).

“The data are striking,” said Akiko Iwasaki, a professor of immunobiology and long Covid researcher at Yale University. Iwasaki was not involved in the study but is also part of PolyBio’s long Covid research group.

Researchers used pre-pandemic scans as a control group, “the cleanest comparison that there is, before anybody on the planet could’ve possibly had this virus,” Peluso said. There were 30 participants in total (24 who’d had Covid, and six controls). Uninfected participants showed some T cell activation, but it showed up in parts of the body that help clear inflammation, like the kidney and liver. In the post-Covid group, immune activation was widespread, even in those who report that they are back to their normal health.

The data don’t explain what exactly T cells are reacting to. As Iwasaki noted, activated T cells can be responding to persistent SARS-CoV-2 antigens or autoantigens found in people with autoimmune disease. The immune response could also be to antigens coming from other pathogens, like the common Epstein-Barr Virus. This piece requires more study, she said.

In the gut, the researchers found what they think is RNA that encodes the virus’s signature spike protein. Other studies have found similar pieces of virus in autopsies, or within a couple of months after infection. Peluso’s work suggests the virus may stay in the body much longer — up to years after infection.

The researchers don’t know if what they’re seeing is “fossilized” leftover virus or active, productive virus. But they found double-stranded RNA in the guts of some patients who underwent biopsy. That should technically only be there if a virus is still alive, going through its life cycle, Peluso said.

Scientists and patient advocates have been suspicious for a while of the gut reservoir post-Covid. This new data may add fuel to the idea that SARS-CoV-2 stays in some people’s guts for a long time and could actually be driving long Covid. Or, on the other hand, it could mean our immune response is failing to clear the virus and leaving behind little pieces (which might not be harmful). There are still a lot of questions, Peluso admitted. But the paper undermines the paradigm that declares Covid infection disappears after two weeks, and long Covid is just residual damage.

The findings also suggest a need for more aggressive evaluation of immunomodulating therapies, and treatments that target leftover virus.

Most researchers hunting for a long Covid biomarker have turned to the blood or small pieces of tissue as surrogates for what’s happening inside a patient. With the new imaging technique, Peluso and his team can see a full person on their screen — a patient’s phantom figure and gauzy organs covered in splotches of light. “It’s really striking,” he said. “‘Oh, my goodness, this is happening in someone’s spinal cord, or their GI tract, or their heart wall, or their lungs.’”

For patients like Ezra Spier, a member of the LIINC cohort who’s had imaging done after the period captured in this latest study, the experience was validating. Finally, the life-changing experience of long Covid had become visible. “I can now see with my own eyes the kind of dysfunction going on throughout my own body,” said Spier, who created a website for long Covid patients to more easily find clinical trials near them.

Most participants had been infected with a pre-Omicron variant of the virus, and one person had repeat infections throughout the study period. Two participants had been hospitalized during their initial bout of Covid, but neither one received intensive care. A half-dozen patients in the study reported zero long Covid symptoms, but still showed elevated levels of immune activation.

The paper does not explain what the sites of infection mean for symptoms, and immune activation in a particular organ doesn’t correspond to symptoms (for example, a gut full of T cells doesn’t necessarily match with GI problems). More studies are needed to figure out what the glowing spots mean for patients’ experience of long Covid.

And the scans don’t work as a diagnostic. In other words, patients shouldn’t rush to San Francisco (Peluso’s group only accepts study participants from the area). The imaging technique isn’t available to the general public, either. F-AraG is still being studied in this context.

But Peluso and Vanbrocklin said imaging could be a major tool in figuring out long Covid. They’ve expanded their research program to do imaging on about 50 additional patients. They are also scanning people before and after they receive different long Covid clinical trial interventions to see if there’s a change in immune activity.

To submit a correction request, please visit our Contact Us page.