Two Democratic lawmakers are pushing the Drug Enforcement Administration to take a more lax approach to regulating buprenorphine, a medication used to treat opioid addiction.

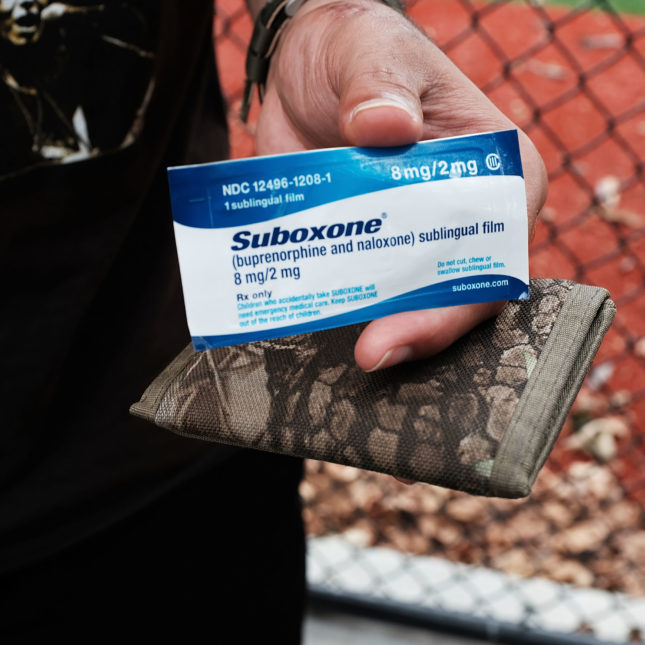

“Bupe,” also known by the brand name Suboxone, is one of just two medications currently approved to treat opioid cravings and withdrawal. And though it is associated with a 38% reduction in risk of opioid death, it remains stigmatized because it is chemically an opioid — and, accordingly, highly scrutinized by the DEA.

But a new legislative proposal introduced this week by Sen. Martin Heinrich (D-N.M.) and Rep. Paul Tonko (D-N.Y.) would force the federal government’s drug police to back off from monitoring buprenorphine the same way it monitors more potent prescription painkillers.

“We need an all-hands-on-deck approach to tackle this epidemic with the urgency it demands, which includes eliminating barriers that providers and patients face in accessing life-saving medication,” Heinrich said in a statement. “My legislation aims to change reporting requirements for buprenorphine, ensuring that patients receive timely and effective treatment for opioid use disorder. This will help save lives and help New Mexicans get the care they need.”

The legislation is called the Broadening Utilization of Proven and Effective Treatment for Recovery Act — the “BUPE Act,” for short. It requires the DEA administrator to exempt buprenorphine from the agency’s Suspicious Order Reporting System, which the agency created in 2019 to combat the oversupply of painkillers behind the first wave of the opioid epidemic.

But the lawmakers argue that SORS may now be backfiring, at least when it comes to buprenorphine. Instead of helping to prevent the oversupply of painkillers known to cause addiction, some drug policy experts now say the DEA system has made it harder to access the very medication used to treat those addictions.

By 2019, prescription opioid volumes had already plummeted, and fatal overdoses resulting from prescription painkillers had begun to fall from their peak in mid-2017. A large majority of opioid deaths, instead, were increasingly caused by illicit fentanyl.

Given the changes in the drug supply and current drivers of overdose death, the lawmakers now argue that the DEA’s stringent requirements are blocking access to a lifesaving medication amid a deadly overdose epidemic.

Though the Biden administration has made access to buprenorphine a cornerstone of its opioid crisis response, patients seeking the medication still report that it is prohibitively difficult to access, in large part because few doctors prescribe it and barely half of retail pharmacies stock it. In a press release, Heinrich’s office argued that “SORS reporting requirements have led to an uncertainty among pharmacies and distributors to stock and dispense buprenorphine.”

The legislation would require the DEA to exclude buprenorphine from SORS until the end of the public health emergency related to the opioid crisis, first declared by President Trump in 2017 and subsequently extended by his administration and President Biden’s.

Once the public health emergency ends, the Department of Justice and Department of Health and Human Services would then conduct an assessment to see whether buprenorphine should be re-included.

A wide array of major medical groups have already endorsed the legislation, including the American Medical Association, American Society of Addiction Medicine, American Pharmacists Association, and Faces and Voices of Recovery.

The bill’s introduction comes amid a broader controversy involving buprenorphine and the DEA — specifically, a set of controversial regulations governing whether health providers should be allowed to prescribe the medication via telehealth.

Heinrich and Tonko’s legislation adds another layer of pressure for the agency, which is already facing a barrage of criticism from lawmakers and addiction treatment groups, pushback from the Department of Health and Human Services, and multiple pieces of legislation that would effectively undercut its attempt to restrict the prescribing of buprenorphine via telehealth.

STAT’s coverage of chronic health issues is supported by a grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies. Our financial supporters are not involved in any decisions about our journalism.