One of the most important measurements for cancer patients is the neutrophil count. Certain cancer therapies like chemotherapy can be harsh on these white blood cells, so cancer patients need their neutrophil count to be in a given range when undergoing those treatments or before enrolling in particular clinical trials. That can be a problem for people who have a natural blood variation called the Duffy-null phenotype.

About 67% of African Americans have the Duffy-null phenotype, which leads them to have a naturally lower level of neutrophils in their blood. It doesn’t affect their health or ability to fight infections, but it can tip their neutrophil counts into a range that would be considered low. That can lead some people with the Duffy-null phenotype to being unfairly excluded from most cancer clinical trials and negatively affect their treatment, according to a new study published in JAMA Network Open on Wednesday.

That inappropriate exclusion may also help to explain the historically low levels of African American cancer clinical trial participation, said Andrew Hantel, a medical oncologist and researcher at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and the senior author on the study. “There’s a number of systemically racist reasons why people are excluded from clinical trials disproportionately,” he said. “This is one piece of that, potentially.”

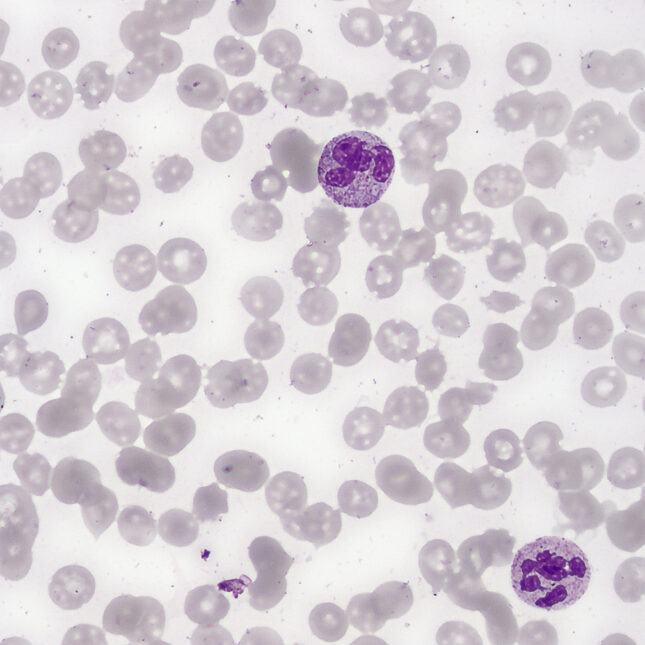

Duffy-null phenotype, which was previously called “the somewhat derogatory term ‘benign ethnic neutropenia,’” Hantel said, is a variation in the red blood cell. It’s most common in places where malaria has been endemic — namely Africa and the Middle East. People with ancestry from these regions are more likely to have the phenotype, which also can lead neutrophils to concentrate more in the spleen and less in the bloodstream than people who aren’t Duffy-null. “So, when we take a tube of blood out of somebody, it looks like they have less neutrophils,” Hantel said.

That can make it appear as though a patient’s immune system is less prepared to fight off infections than it is. Neutrophils are one of the body’s first responders against viruses and bacteria, and their numbers give physicians a sense of how competent the immune system is. Low counts might suggest the patient is vulnerable to serious infections, and that it would be dangerous to give chemotherapy or other drugs or include them on clinical trials for drugs that might lower neutrophil levels.

“That concern is why lots of trials have neutrophil criteria in them,” Hantel said. “And after a trial leads to drug approval, we might delay the drug or reduce the dose or omit the drug entirely if somebody’s neutrophils go too low or remain low.” That applies to practically every drug that impacts neutrophil counts, Hantel added.

But when Hantel and his colleagues looked at hundreds of cancer clinical trials done between 2021 and 2023, they didn’t find a single protocol that accounted for the different, healthy neutrophil range for people with a Duffy-null phenotype. That’s despite the fact that norms for adequate neutrophil ranges in the United States are based on people who don’t have the phenotype. Instead, the team found that of over 289 trials, 76.5% contained criteria that would exclude people who would naturally fall on the lower end of a healthy Duffy-null neutrophil range.

When the team looked at protocols for drug regimens that instructed physicians to modify dosing, they found 53.5% of 71 regimens recommended dose modifications based on neutrophil counts that could negatively impact Duffy-null individuals. “If you reduce somebody’s dose intensity on chemotherapy, they have inferior overall survival,” Hantel said.

The study highlights how medical norms based on European ancestry populations may lead to harm and bias against certain other populations, said Consuelo Wilkins, a physician and health equity expert at Vanderbilt University who did not work on the study. “This is specifically medical racism. I would say, in terms of structural racism, this is a reference range determined within a clinical or medical setting, and it’s disproportionately impacting people,” she said.

It is also only one such example, Wilkins added. There are numerous other factors that can lead to exclusion of marginalized and minority communities from clinical trial participation, including requirements for language or transportation. “Those social factors somehow creep into the inclusion-exclusion criteria,” Wilkins said. “Your insurance status can determine whether you can participate. That’s an example of structural racism. Some trials require a social security number. That is structural racism.”

And they are all things that can be struck from trial participation criteria to make medical research more inclusive. Hantel offered an example from another benign condition, Gilbert’s syndrome. This condition can lead to elevated bilirubin levels; high levels of this compound could indicate liver or biliary disease. Gilbert’s syndrome “predominantly impacts white individuals,” Hantel said. “There are carveouts for dose modifications and eligibility for trials. If you have Gilbert’s, you are allowed on even if your bilirubin is higher. It’s an interesting, disappointing analogy.”

Hantel can’t think of a good reason why trials being designed now can’t include similar exceptions and conditions for Duffy-null individuals. For cancer therapies and regimens that are already approved, Hantel said physicians and scientists should work on understanding appropriate neutrophil ranges for people with Duffy-null phenotype.

That, he hopes, will bring about more accurate, and fairer, treatment of cancer patients with African or Middle Eastern ancestry.