When a dye called tartrazine is added to food, it creates a bright yellow hue often associated with lemon-flavored candy. But when mixed with a little water and daubed on the skin of mice, the dye makes their skin nearly transparent.

Researchers reported the new use for the common food dye today in the journal Science. The technique creates a fresh opportunity for researchers to understand what is going on under the skin of a live animal, which could eventually allow them to study the inner workings of large organs or how diseases change the body.

“The application here is definitely on the live sample side. With the tissue clearing methods that we have right now, for the most part, you don’t do live stuff,” said Douglas Richardson, a senior research scientist at Harvard’s Center for Biological Imaging who was not part of the new work. “So it’s really opening a new avenue there.”

Tissue clearing isn’t a new idea — researchers as far back as 1914 were mixing chemicals to make tissue transparent. But researchers have historically been limited to working with samples of dead tissue because the chemicals — mostly different kinds of acids and alcohols — were not safe for living creatures.

The key to tissue clearing lies in changing the way light passes through tissue. Tissue is usually not transparent because light moves through water, lipids, and proteins — the three main components of tissue — at different speeds. Tissue clearing works by making light move at similar speeds through all the different components of tissue, so light can pass right through them. When the technique is combined with high-powered microscopes, it allows scientists to see deep tissue in more detail than other imaging techniques like CT scans or MRIs.

The new method, researchers say, might seem counterintuitive. “We usually expect dye molecules to make things less transparent,” said Guosong Hong, a materials science professor at Stanford University and senior author on the paper. “When we dissolve tartrazine in an opaque material like muscle or skin, which normally scatters light, the more tartrazine we add, the clearer the material becomes.”

The researchers started from a theoretical framework that suggested molecules absorbing light at a specific wavelength of light could “actually change some part of the optical properties in the tissue that leads to improved transparency,” said Zihao Ou, an assistant professor of physics at the University of Texas at Dallas and lead author of the study. The team was skeptical the method would work, so Ou set out to test their theory by applying different dyes to chicken breast. “I brought my knife and cutting board to the lab,” he said. “And I was marinating chicken breast in different dye solutions.”

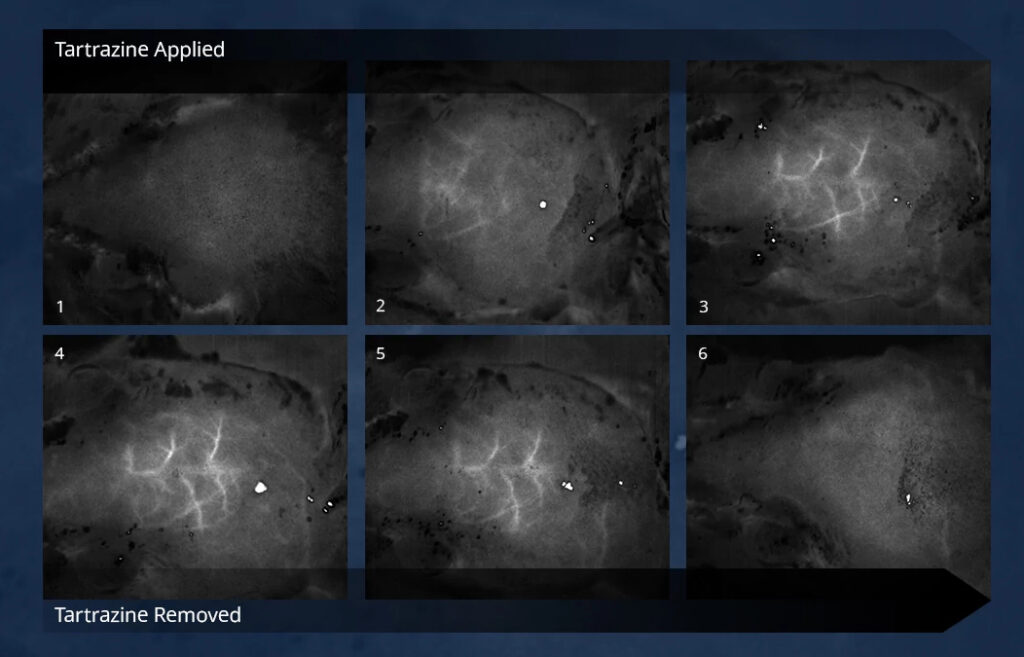

Hong and Ou’s team settled on tartrazine because it made tissues transparent in the visible spectrum. Within five minutes of massaging the solution on the mice, they could see through them with the naked eye. But their technique could be used with different dyes to make tissue transparent in different spectrums of light.

The technique holds potential, said Ali Ertürk, the director of the Institute for Tissue Engineering & Regenerative Medicine at Helmholtz Munich, who has developed other tissue clearing methods and was not involved in the study. But “substantial further research is required to establish its safety, efficacy, and practical benefits.” One concern is how deeply the dye is absorbed into the body, and any long-term effects of exposure to the dye.

The method is noninvasive and reversible: It just requires rubbing a dye solution on the surface of a tissue and then can be washed away when scientists are done imaging. For those reasons, researchers say it could unlock new areas of study — for example, following the inner workings of an animal over longer periods of time. (For thicker and less permeable skin, like that of humans, the dye if proven safe could be injected to reach deeper layers of tissue.)

“It’s been really exciting to watch the field over the last decade,” Richardson said. “All biology is 3D and this really allows you to better appreciate the three-dimensional anatomy of a tissue.”