A year ago, after much fanfare and controversy, the Food and Drug Administration approved Eisai and Biogen’s lecanemab, an anti-amyloid drug that moderately slowed cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. But doctors have been hesitant to prescribe the drug and its pharmacological cousin, Eli Lilly’s donanemab, for people with Down syndrome because of a lack of safety data.

The treatment delay might be helpful, however. When researchers treated post-mortem brain tissue of people with Down syndrome with lecanemab, they determined that this population might face higher risk factors. Compared to the general population, their cerebral vasculature could put them at a higher risk of brain hemorrhages and brain swelling — the same side effects the FDA discussed when it approved the drug.

Proceeding with caution is important here, said Lei Liu, the study’s lead author and a neurologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

“We clearly understand that there is a correlation with brain blood vessels and amyloid deposits with side effects of these types of drugs. We started to worry that if we give the Down syndrome patient this type of medicine, they will have stronger side effects,” said Liu. “We wanted to investigate if this drug will bind to the blood vessels.”

Even though researchers like Liu understand that risk theoretically, there’s scant data on it because people with Down Syndrome — the population with the highest prevalence of the disease — are historically excluded from clinical trials. The data generated by the new study, and other future studies, could eventually help make life-extending Alzheimer’s drugs like lecanemab available to this population group that faces a 90% lifetime risk of developing the neurodegenerative disease.

Over 18,000 people have participated in drug trials for these anti-amyloid antibodies, according to research from LuMind IDSC, a group that advocates for better Down syndrome research. Not a single participant had Down syndrome. Most people with Down syndrome have an extra copy of the 21st chromosome, which contains the gene that codes for the amyloid precursor protein. From birth, their genes make more of the protein that is the hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease.

LuMind IDSC president Hampus Hillerstrom says this research disparity must change. Alzheimer’s is so prevalent in the Down syndrome community that a 2023 RAND study found that these therapies could eventually increase an individual’s average lifespan without the disease by five years. Caregiving for people over 45 years old with Down syndrome also costs $1 billion annually. But Hillerstrom doesn’t want the potential benefits to come at the expense of people’s lives.

“This kind of finding needs to be taken into consideration when you’re planning a study…of future clinical trials in [people with] Down syndrome,” said Lon Schneider, who directs the USC California Alzheimer’s Disease Center and was unaffiliated with the study. “It might also be a bit of a warning.”

The study, published in JAMA, analyzed postmortem brain tissue from 15 individuals with Down syndrome aged 43 to 68 years with Alzheimer’s disease. When researchers injected lecanemab into the tissue, the antibody readily bound with the amyloid deposits. This is what the drug is designed to do, prohibit these amyloid plaque deposits from forming.

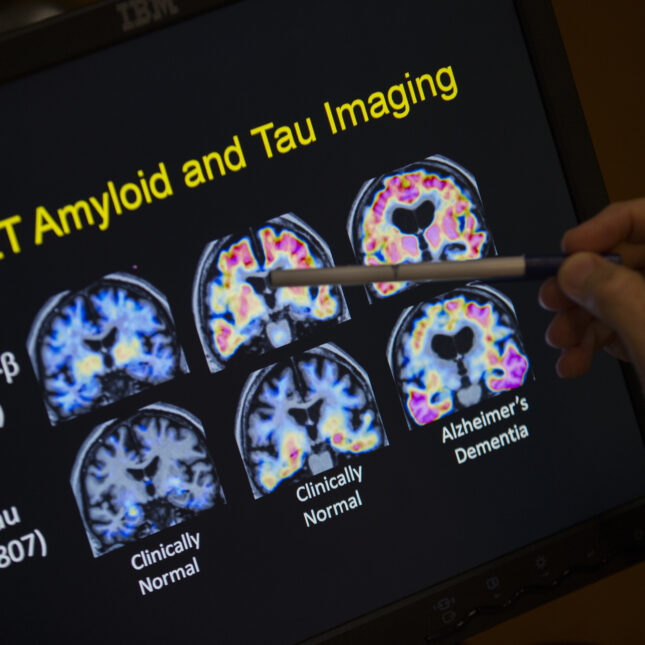

However, people with Down syndrome have higher levels of cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) — meaning, their brain’s blood vessels naturally swell up with this protein. These protein deposits weaken vessel walls, leaving them prone to leakage, i.e., a hemorrhage. Brain hemorrhages are uncommon with Alzheimer’s disease, but studies of lecanemab in the general population found higher associations between the presence of CAAs and hemorrhages. Serious complications occur in less than 1% of patients, even though there have been a few, potentially related, deaths. So Liu hopes researchers proceed with caution when treating and dosing people with Down syndrome.

Experts say that it is still an open question how Alzheimer’s manifests in people with Down syndrome compared to the general population. The researchers did not test how tissue from people without Down syndrome or without Alzheimer’s disease fared.

While none of the existing anti-amyloid drug trials have included people with Down syndrome, the companies behind these drugs say they have not explicitly excluded that population. Sometimes, the younger presentation age of the disease in many people with Down syndrome has kept them from qualifying for trials, which, by one account, had a mean average age of 72. The average life expectancy for someone with Down syndrome is 60. Guidance from LuMind IDSC and the National Task Group on Dementia recommends that future trials lower the age thresholds.

But the scientific community will not have to wait long to see the effects of these drugs on real people instead of tissue cultures. The first trial of donanemab in people with Down syndrome is slated to begin in 2025, according to one of its principal investigators, Michael Rafii, a neurologist at University of Southern California. He said that they are aware of the elevated risk factors seen in Liu’s study and plan to proceed with caution.

“This is a critically important study and further confirms that safety trials of the amyloid-lowering antibodies must be conducted in people with [Down syndrome] before they are prescribed in the clinic,” said Rafii.

STAT’s coverage of disability issues is supported by grants from Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and The Commonwealth Fund. Our financial supporters are not involved in any decisions about our journalism.