CHICAGO — The last place you might have expected Kevin Hall to make a plea for help was at a conference of scientists who work for global food conglomerates. After all, the government researcher is the leading scientific voice in the United States warning that a steady diet of these engineered products might be a crucial driver of the nation’s epidemic of overeating.

Yet there he was earlier this summer at Chicago’s cavernous McCormick Place convention center, alongside salesmen for Cargill pitching their high oleic canola oil, asking food technologists to partner with the government to investigate the health impact of these foods.

“I need some buy-in from folks in the audience,” Hall told a half-full conference room.

Hall’s work at the National Institutes of Health presents an existential challenge to the food industry, which has staked its business model for decades on developing ultra-processed meals that are cheap, easy to prepare — and let’s face it — delicious. That he was now trying to drum up interest from those same food makers in a yet-to-be-finalized program funded by an “unnamed government agency” might have seemed naive to some, but it was also a sign of his eagerness to supersize research into industrial creations like sodas and breakfast cereals — a line of inquiry he and some nutritionists consider vital for public health.

“I can keep doing my studies but at the rate that these are going, it’s going to take forever to figure this out,” Hall told STAT. “We don’t have forever. Chronic diet-related diseases are costing us a huge amount of money and a huge amount of suffering.”

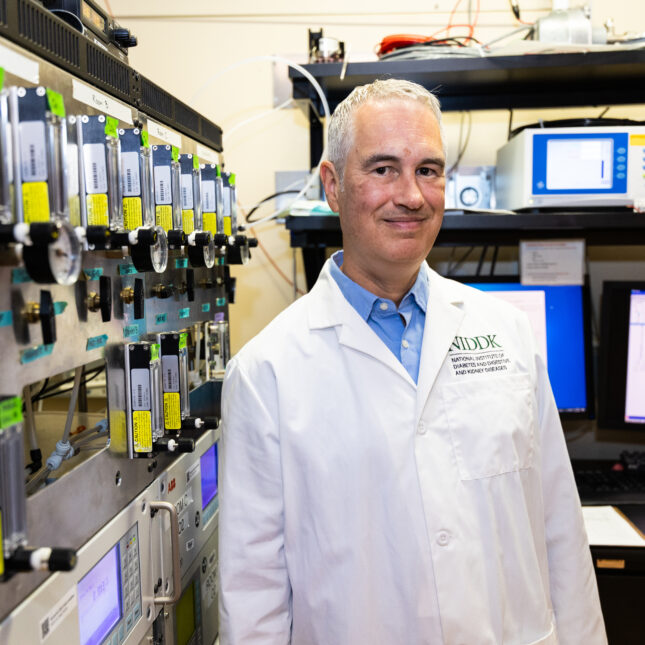

Many other scientists would envy Hall, 53. He has tenure at one of the world’s most prestigious research institutions and a team of dieticians, graduate students, postdocs, and even cooks to execute his experiments. The team controls what subjects eat for a month to ascertain whether an ultra-processed diet of foods like chicken fingers and mac and cheese prompts people to eat more than they would when fed unprocessed foods.

But, it’s slow work. Hall’s first study took a year. His newest study, of just 36 people, won’t be done until the end of 2025.

The NIH invested just over $2 billion on nutrition research last year. That includes both research, like Hall’s, done in government facilities, and grants to outside scientists at universities. The agency, meanwhile, spent nearly $11.9 billion on neuroscience, $8.9 billion on brain disorders, and $5.1 billion on neurodegenerative diseases.

Hall’s current study is operating with just two beds in the NIH’s clinical hospital and its nine miles of sprawling corridors.

“The idea that the NIH isn’t sinking a fortune into this is just shocking to me,” said Marion Nestle, an emeritus professor of nutrition and public health at New York University, who called Hall’s first clinical trial on ultra-processed foods “the most important study in nutrition that’s been done since vitamins.”

Hall, for his part, lauds NIH leadership, which encouraged him — a physicist with a background in experimental computer modeling of diseases — to start heading up his own clinical trials a decade earlier.

“Where else on earth would a person with no M.D., no clinical training whatsoever … be given the opportunity to lead a clinical study?” Hall said.

When asked about his budget, he added: “The nice thing about being at the NIH is that we have stable funding — but the issue is that it’s stable funding.”

Hall’s career path, he admits, “has been kind of stumbling in directions that are interesting … and asking questions that folks in those disciplines have not necessarily asked.”

A self-proclaimed “failed physicist,” he began his career among a clique of academics intent on applying chaos theory to cardiology care. His Ph.D. thesis, which he began by thanking his mentors for keeping him from studying particle physics, hypothesized a new more accurate method for more precisely detecting and controlling heart arrhythmias. He said the method, which he learned later was also used to locate enemy cannons in World War I, was eventually patented by a company (whose name he has since forgotten) “that got sold for like $100 million or something.”

Hall got nothing, except some early academic publications with titles like “How to Tell a Target from a Spiral: The Two Probe Problem,” and eventually a job at a startup that was developing computer simulations to model diseases.

“They hired me to lead their type 2 diabetes program,” Hall said. “I’m like, what’s diabetes?”

He joined NIH in 2003. The agency was just building the metabolic ward where Hall now conducts his experiments, and he pitched his ability to model the outcomes of experiments that he hoped would be conducted using the new equipment.

“The scientific director at the time said, ‘Yeah, well, that’s great. Why don’t you do those experiments?’” Hall said. “I thought you had to be an M.D. to do this.”

Soon he found himself studying long-term metabolic adaptation in patients who competed on NBC’s “The Biggest Loser,” the prime time reality show that combined the game play of “Survivor” with scenes of muscled trainers screaming at morbidly obese people to do sit-ups — to see who could shed the most pounds.

Hall’s first study on ultra-processed foods — for which he is now most known — was actually an attempt to disprove concerns about ultra-processed diets. It grew out of a talk he gave on an earlier controlled-feeding trial, in which obese patients were put on a carb-restricted diet and then a fat-restricted diet to determine which led them to shed more fat. Afterward, two dietitians from Brazil suggested he was approaching the issue all wrong.

“These dietitians from Brazil said, ‘Your talk was really interesting, but why are you still talking about nutrients?’” Hall recalled. “‘That’s like a very 20th century way of thinking.’”

“I was like, ‘nutrition is about nutrients,’” Hall added.

The subsequent study ended up bolstering the Brazilians’ concerns about ultra-processed foods. Hall and his team had housed 20 adults at the NIH’s clinical hospital for 28 days. For half the time, participants were fed a diet of ultra-processed foods, and the other half, they got unprocessed foods. Participants had no control over what they ate, except that they could eat as much or as little of what they were presented as they wanted. The study found that people ate, on average, over 500 calories more on the ultra-processed diet.

The results made Hall a minor celebrity by NIH standards. His research has been featured in the New York Times, Business Insider, the Wall Street Journal, and the documentary Food Inc. II.

In the world of nutrition — where definitive headlines often proclaim findings that are at best equivocal and at worst misleading — Hall’s research provides a clear takeaway for the public.

“The take-home lesson from this was absolutely unambiguous: If you’re worried about weight, don’t eat ultra-processed foods,” Nestle said. “To get an answer like that in a nutrition study, that’s unbelievable.”

While his initial study involved only 20 people, his methodology of strictly controlling the types of food they could eat stands out in a discipline that relies heavily on epidemiological studies and basic science research that cannot definitively show a food causes benefit or harm.

Hall is still one of the only researchers doing controlled feeding trials for ultra-processed foods. A few trials unaffiliated with Hall are underway in Virginia, London, and the Netherlands.

However, Hall’s mass appeal doesn’t exactly resonate with the everyday nutrition community.

Prominent nutrition scientists have challenged Hall’s conclusions, claiming that the weight gain documented in his first study would likely moderate over time if he followed people for longer.

“Studies on diet, energy balance, and body weight lasting only two weeks are less than useless because they are likely to be seriously misleading,” said Walter Willett, a professor at the Harvard School of Public Health and the most-cited nutritionist in the world. “It is hard to understand why the NIH has continued to fund two-week studies of diet and energy-balance.”

Some of the resistance to Hall’s research is likely the result of academic inertia, according to Carlos Augusto Monteiro, a professor of nutrition and public health at the University of São Paulo who is widely credited with pioneering research into ultra-processed foods. The focus on processing challenges decades of research that has focused almost exclusively on certain nutrients — sodium, fat, sugar — as the main causes of dietary ills.

“They resist in a way, because it is like they are losing some power,” said Monteiro. “We are all human beings, so it is understandable.”

Hall, too, said many of the academics he expected to be most interested in investigating this new idea are the ones most entrenched in their previous beliefs.

“I thought … nutrition scientists would be like, ‘Yeah, we’ve got to do something about this,’” he said. “But instead it’s like, ‘Oh, no, it’s just the carbs that are the problem. It’s really just the sugar. It’s really just energy density.’”

Hall let out a titter while attempting to traverse the quartet of musicians in purple sequin evening gowns at the entrance of the Institute of Food Technologists exhibit hall, plucking away at the hook of Dua Lipa’s “Levitating.”

He was set to give one of the opening keynote addresses later that day for the 17,000-person gathering, where more than 1,000 companies were showing off their latest inventions. Virtually all of them would qualify as ultra-processed, which are products defined as being “made mostly or entirely from substances derived from foods and additives, with little if any intact [unprocessed] foods.”

When the term is mentioned by food industry allies over the next few days, it is a euphemism for bad science — like fear of genetically modified organisms or the belief that eating an “ancestral diet” of meat and only meat will improve your blood pressure. Much of the industry says the science on the ills of ultra-processed foods is too nascent to warrant action, or worry.

Hall insists the industry should have an interest in his work, and that his research on how these foods might prompt weight gain could help companies redesign their products. “You could have situations where you have healthy ultra-processed foods,” he says.

“Sounds tough to me,” said NYU’s Nestle when told about Hall’s efforts. “The food industry has no interest whatsoever in doing research that will prove unpleasant for their bottom line.”

Two years ago, Hall shared the same conference stage with Nestle to debate proponents of ultra-processed foods about whether people should cut down, or increase, their intake of these products. Hall acknowledged the need for processing, but argued that it defied logic to suggest that Americans need to eat more of these industrial creations, which already make up roughly 60% of the calories in an American diet. By the end of the hour, a poll showed Hall and Nestle had won over less than half the audience.

Outside a multi-colored Kraft booth where dozens of people were lining up beneath hulking ketchup bottles for personalized versions of the ultra-processed condiment, he lamented his situation.

“If it takes me 2.5 years to do a study of 36 people … I’ll be retired before we figure out the first couple of things,” Hall said.

But then he mentions the idea of renting a retreat center where he could house and study dozens of people at a time rather than just two. He already has a location picked out — a conference center in Virginia — and is pressing NIH to let him rent it, though he admits scraping the money together will be tough.

Hall is also here to pitch food makers on a separate idea, to have another government agency dole out funding to the private sector so it could investigate ultra-processed foods. Hall declined to name the government agency because the proposal is still in the early stages, and has not been publicly announced.

A few minutes later, a fireside chat kicks off at the back of the exhibit hall on NIH funding, or lack thereof, for nutrition research.

“Nutrition funding represents around 4 to 5% of total obligations from the NIH,” a speaker tells a small group huddled around a faux campfire. “Which is like — compared to the impact that nutrition and food can have — just a really low number.”

STAT’s coverage of chronic health issues is supported by a grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies. Our financial supporters are not involved in any decisions about our journalism.

To submit a correction request, please visit our Contact Us page.